Dick Eggerding: The Man Who Made Oro Valley Sing

In 1994, Oro Valley was still a small suburban community of the greater Tucson area. For the first time, the population exceeded 5,000. The timing and political environment were conducive to exciting and progressive ideas related to fine arts and overall cultural development.

The town council appointed an arts advisory board in October 1994, and, that same year, the Arizona Commission on the Arts was engaged to prepare a “Community Cultural Assessment.” The results of the study would prove pivotal in adopting a public art policy.

After the mayor and council accepted the results of the cultural assessment, steps were taken to research possible action on cultural quality-of-life issues.

The final report made several key suggestions, one of which was: “… consider the possibility of establishing a percent for public art program.” Such a program would require that all public and commercial construction projects allocate 1 percent of total building costs for on-site public art. A concentrated effort began to find other communities in Arizona and elsewhere that had such a requirement. Tempe, Arizona, was one such community. It provided the motivation to create a town code establishing a 1 percent for public art set-aside in Oro Valley for all public and commercial construction.

1996, the general plan advisory committee proposed that the town “adopt and implement a 1-percent-for-art ordinance.” A time frame of one to three years was suggested. The importance of having had the subject in the general plan cannot be overstated, because of the official recognition it unanimously received from the council.

In May 1997, a town code was adopted that would require a 1 percent for public art program. The code would mandate that an amount equal to 1 percent of the budget of all commercial developments and public works projects be spent to develop public art. The code was quite specific as to what acceptable art was and how it should be displayed. It also provided for a public art review committee (PARC), which would review all public art submissions by the town and commercial developers. The PARC has since evolved from a committee into a commission. The arts advisory board proposed the new town code, and it passed unanimously on September 3, 1997. By creating economic opportunities for artists, Oro Valley has cemented its reputation for strongly supporting the arts.

In addition to commercial developments, further public art was sought out and, in 1995, the Pima Association of Governments made available funds for summer youth art projects concurrent with the passage of the public art code that would employ students during the summer to work in all facets of design and installation of a public art piece in Oro Valley.

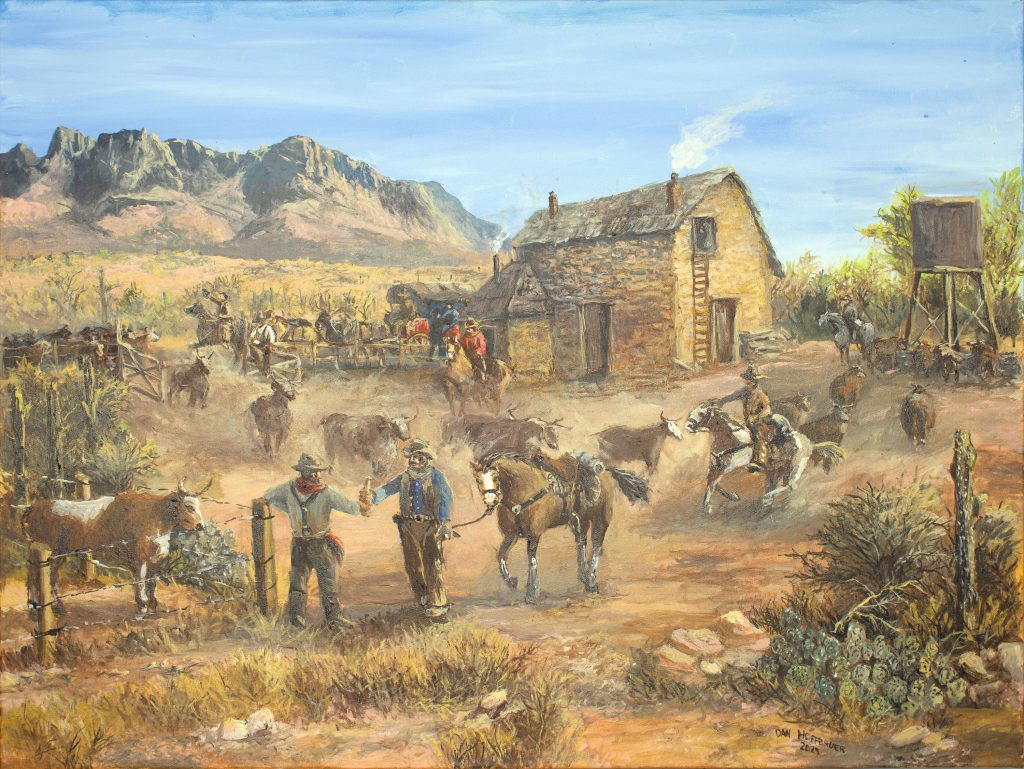

As you drive around Oro Valley, you will see three types of public art: works adorning commercial building sites, youth summer public art projects in parks and along roads, and art on town-owned sites and roadways.

Dick Eggerding is the co-founder, with Robert “Bob” Weede, and the president emeritus of the Greater Oro Valley Arts Council, which evolved to the Southern Arizona Arts and Cultural Alliance in 2009.

Watch the video, Dick Eggerding – The Muse of Tucson as Dick Eggerding recounts how he helped shape the cultural and artistic landscape of Oro Valley, from founding the arts council in 1997 to launching major public art initiatives, organizing large-scale community events like the 2003 Fourth of July symphony and fireworks show, and advocating for the town’s 1% for public art ordinance. It’s a firsthand look at the passion, persistence, and partnerships that built a lasting arts legacy. (Scroll down for rough transcript of the interview.)

Resource:

Excellence by Design Picture Book

EXCELLENCE BY DESIGN – A Visual History of Public Art in Oro Valley, Arizona

Created by the Southern Arizona Arts and Cultural Alliance (SAACA), this book features:

- Biographical information about local artists

- Artists’ personal statements

- Locations of public artworks throughout Oro Valley

Find it at Pima County Public Library or Amazon.

Read more:

Featured Citizen, The Many Hats of Dick Eggerding (By Tom Ekman, J.D., M.Ed., May 2023)

Oro Valley’s 1% for Public Art Program: Commercial Construction

Take this walking tour to explore the public art at Steam Pump Ranch and Steam Pump Village!

An interview with Dick Eggerding – January 2023

I was born in St. Louis, Missouri. My father’s name was Ted and my mother’s name was Clara, and my mother was an opera singer and she studied with the same voice teacher that Helen Traubel did, who was a famous Wagnerian soprano. So, we had music from the get-go in my house.

My father was in the military in 1918 and he did get the Spanish flu in the trenches and he got a medical discharge, and in those days, they didn’t have the vaccine so it just kind of wore itself out. And he really didn’t know what the results of the flu had been on him, and as it turned out, it enlarged his heart, and as he got older it took its toll. And when I was two years old, he died from that ailment.

And my mother raised my brother and I in the middle of the Depression during that whole time. And one of the most influential people that I had was my grandfather, who was a judge, and he was also a consummate reader of fine arts. And he was always trying to get me to do things in the fine art area as well as my mother.

So, I was raised singing and my brother was a baritone and I was a tenor, and my mother was a mezzo soprano. So, we would do all kinds of musical events together—at churches in particular, but also in German what they call Lieder. In St. Louis these are singing groups. So, I can honestly say I’ve been singing since I was 16 years old.

The Depression took its toll, obviously. Thankfully my father started an automobile dealership and so it left my mother in pretty good shape. We lived a pretty good life—upper middle-class life, actually. And this went on quite a while in terms of what we were exposed to. That is, the Depression was horrible to observe as a little kid. People would come to our door asking for food, and my mother had a brother who had a butcher shop, so we always had plenty of food. And she would make sandwiches every morning when she got up because she knew somebody would knock on our door and want a sandwich.

So, I went through that entire era of being exposed to that, and it really didn’t end till World War II. And of course that was a dramatic thing too. My mother had ten brothers and sisters. They had lots of kids, obviously, so I had a lot of cousins, many of whom went into the war. Two or three of them were wounded—one in Anzio in Italy, one in Bastogne. People like that. And when they came out, it left quite an impact on all of us. So that’s my story of the Depression.

Well obviously, during my high school years my voice changed and I developed a tenor voice, and I was able to get into a lot of operas and light operas at the time because my mother could get me into shows. So, I sang a great deal while I was in high school, and I also met my wife in high school, and we’ve been married 67 years, and I’ve known her for 70 years.

As far as exposing me to the arts, my mother never failed to take me to art museums and that type of thing when we traveled. And I really developed a love of art—period—just all kinds of art. And when I went to college at Washington University in St. Louis, I had a music scholarship for singing, and I worked in the art store. And I got to meet all of these famous artists who were guest lecturers, and it was very fascinating to get to know a lot of these artists.

So that whole time that I was growing up I was exposed to not only music but to fine arts as well, which would play out later on in my life.

So fast forward to the Korean War. Okay, stationed in Japan. What did you do to make a difference there?

Let me begin to the point where I entered the military. My wife and I were married when we were 21 years old. I was deferred through most of the war, and after we were married and I lost all my deferments, then I volunteered for the draft because they told me I was going to be drafted in a couple of months.

So, I went in and did my basic training. They had me down as an opera singer—which I was at the time when I went in—but that was what my MOS was on the military documents. I ended up playing the organ. I used to play the piano, so the churches on the posts where I was had these electric organs. I volunteered on Sundays to play the organ and sing and so forth, and I did that for almost a year while doing other duties within the service.

As luck would have it, one week before my term would have run out—before they could send me overseas—they sent me overseas. One week! If I had just waited one more week, I never would have gone overseas.

That leads me to one of the most challenging times of my life. They moved me up to Fort Lewis in Washington State, which was a disembarkation point for the Far East. I was leaving there on a Liberty ship converted into a troop ship called the Freeman. We got out onto the Pacific and were heading for Adak to pick up some more troops, and we hit some heavy storms. The ship was just pitching and rolling and going up and down. It was going so high out of the water you could hear the screws spinning.

As luck would have it, another Liberty ship—a sister ship—called the Washington Mail was coming from Adak toward us, and it split in half. We were on an emergency run to go there to see if we could pick any of them up. And here again, as luck would have it, we got to the ship, and all of the crew and passengers were on the bow of the ship. It had water-sealed compartments, so the bow was just bouncing up and down. We strung some buoys going from our ship to their ship and got everybody off that bow onto our ship.

That was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. The interesting thing was there were four priests from Belgium and six nuns from Belgium, and we were able to save all of them. So needless to say, the next morning there was a mass, and everybody was there. That was my first introduction to the military, as far as a desperate experience is concerned.

When I got to Japan, they didn’t really know whether to send me to Korea or to South Japan on an Air Force base, because at that time, all the troops had been discharged and there were a lot of empty positions. They sent me down to what was called a G2—which is an intelligence position—and I really had no intelligence training whatsoever, but I took it anyway.

So, I’m sitting there, and I’m on this Air Force base— Itazuke Air Force Base—which is the same base that Ted Williams and some of the other stars flew out of when they were fighting in Korea. I was able then to get involved—here again—with churches. I would play the organ and conduct choirs and stuff like that.

Then I was given a job to do some TDY work over in Korea, and it all had to do with prisoners who didn’t escape. We never could understand why prisoners never escaped from North Korea. I worked for a fellow by the name of Lieutenant Colonel Meyer, who did a lot of research on it, and his research led to a thing called the Code of Conduct.

The Code of Conduct is a—well, I guess you would call it a pledge—that every military person who goes into the military after the Korean War had to raise their hand and say: I will never surrender, and so forth—all of those good things that you would expect out of a military person. But they actually had to write it all down, because no prisoners ever escaped from North Korea. And that’s a whole story in itself, by the way and then I did further TDI work down in India and Hong Kong so forth and the interesting thing was I was able to observe a lot of the musical history of those countries and I was intrigued by it and Japanese music as well. So, it—the final story for my military service has to do with an orphanage.

I observed as I was traveling around the country in India and other places where we had military, there were some illegitimate children unfortunately, and those children were ostracized. They were never accepted into society as you and I would know it, and in Japan it was doubly worse. And in the town of Huaw where I was located, I ran into some Baptist ministers who had a chapel and a missionary. And I told them about this problem and I said, “Can’t we do something about it?” And they said, “Yes, we could start an orphanage.” So, if you could find the money—and I laughed—I said, “I’m a corporal, how am I going to find the money?”

So, I went to the chaplain and he said, “Well Dick, I think I could help you.” And he went to the commanding officer of both the Air Force— Itazuke Air Force—and the Army. And I was allowed to station myself on payday at the end of the line when the troops came through to pick up their script—their military script. And I had this big sign: “Donate to the orphanage.” And I was astonished at the donations that I got.

And we were able to obtain a piece of land outside of Fukuoka, and the two missionaries went out there and they raised crops and they ended up with 34 of these children. And they were just beautiful children. And we ended up paying for the land, and we ended up paying for the house that they built—all from donations from the military. So, in essence, that was my military career.

In 1955 December, I was sitting over in Japan, and thanks to my connections with some of the higher officers, they arranged for me to fly home—that I didn’t have to take a surface vessel, thank God. So, I flew home and got to California, and it was on December 22nd and it was late at night. And I thought, “Oh boy, I’m going to have to stay there.” And it was a major, and he got me a ticket on a plane to Kansas City. So, I figured I’ll take that just because it’s closer to home.

I got to Kansas City in the morning, and I was able to catch a train on Christmas Eve to St. Louis. And I got back there at 2:00 p.m. in the afternoon and walked in on my wife and family who were celebrating Christmas Eve. They had no idea I was coming. And it was quite a homecoming—it was wonderful. And my wife knew I was eventually coming home, so she had arranged for an apartment for us to live in, and she also had a job at the time.

My dream when I got home was just to acclimate to civilian life. Because when you’ve had that intense—that intense activity that I had for those two years—and it was intense—it leaves an impression on you. And as a matter of fact, I had a lot of fellow friends who were in combat itself, who I got to stay in touch with, and they had a lot of problems. And I—one of my dreams was at that time: How can I help people like that?

I got into a kick. I just really wanted to do work that would be volunteer work, and I tried all kinds of things, but it didn’t work. So, it ended up with a friend of mine who ran a large insurance company. He says, “Come and I’ll teach you the insurance business.” And he did. And to make a long story short, he taught me the commercial insurance business and I went up through the ranks through some various companies. I worked for two very large insurance companies—one was in Seattle – Safeco, and another one was the St. Paul, which is out of Minneapolis. And I worked for some agencies. I spent 35 years in the insurance business.

In this interim, we had two children—two boys, Eric and Tom. And my wife went back to college and got a master’s degree in psychotherapy and became very involved with that type of thing.

In St. Louis though, you had wanted to get into the opera.

I did. I was all—I’m sorry, I didn’t explain that very well. During this time frame I continued my singing. In fact, I oftentimes would fill in once—like the symphony would have a fundraiser and they would have a superstar come in, and one of my thrills of life was Richard Rogers, the composer, came in and they used him as a fundraiser to conduct the symphony. And we had backup singers, and I was lucky enough to sing with Richard Rogers. And that was the thrill of a lifetime.

Yes, I sang a lot. I joined the opera guild, and I joined a German male singing chorus, sang at church, sang with my mother and my brother all of this time frame. And it was exciting—it was very exciting. But in order to succeed in that business, you couldn’t be married with kids—you really couldn’t. You had to dedicate—what you had to dedicate—to get the job done. And I would have to have gone to places like, say, Juilliard or New York or someplace like that to really develop what I should have developed.

Okay. And finally, you moved to Oro Valley in 1988. What brought you here?

Okay. We have lived all over the United States. I traveled and transferred. We built 12 homes in our marriage. And we were exposed to Arizona because Margie’s mother retired in Scottsdale, and we loved Arizona from the get-go. And finally, we were given the decision to make: where would we like to be? And we came to Scottsdale.

And my wife was still active—I had retired—but my wife was still active in psychotherapy. She enjoyed her work, and there was a place here called Sierra Tucson, which is out on Golden Ranch. And she saw an ad and a friend remarked that she ought to look into that because she’s good at what she did. So, she went down here, and I accompanied her, and we drove down the highway. And the first thing we saw were those mountains, and we thought, “Oh wow, isn’t that something?” And then she drove out to Sierra Tucson, which took you out along the mountains, and she saw this wonderful place. And they hired her on the spot almost.

And so we—we were going to live in Scottsdale but we changed our minds and came down here. And we’ve been here since 1988. I’ve been involved with the town since 1990—31 years.

It didn’t take long for you to become a force in Oro Valley. How did that come about?

Well, I don’t know about a force. But I—well originally, my first—my first involvement with getting involved was with the HOAs. We built a home in the Villages of La Cañada. I was one of the first presidents of that HOA. That’s how I got involved originally.

And then there was the town council at the time who were passing laws that affected HOAs. So, I got myself right up there and I started speaking out on my HOA, defending what they were doing. And so that’s how I really got introduced. Now bear in mind, when we moved here there were 5,000 people. And the only grocery stores at the time in 1988—where Marshall’s store is now—was a Safeway. And where the little Walmart is on McGee, that was a Fry’s. And those were the two grocery stores at the time when we were here.

And there was another grocery store that eventually located on Lambert and La Canada before it became a Fry’s. And it was intriguing because everything was so compact and small. Everybody knew everybody. And I used to go up and hang out at town hall when the town was first built. You could just walk in and sit down and talk to anybody. There wasn’t any worry about crime, there wasn’t any worry about disease or anything and I got to know the town manager really well I got to know some of the council members really well some of them and Jim Kriegh, the founder of the town, would hang out up there so it was very easy to get an early start up there. So, after that after I got involved with the HOA’s and then met some of the people at town council I did meet people like Paul Loomis who himself was being active. I remember he was fighting an apartment complex that was going to go up and it was {To Paul, Dick turns to Paul Loomis and states: “I think I’m correct in it am I part, Paul”]. And I was trying to help him because I got him access to my HOA and he come in and make speeches about it and that apartment complex became CEO of Riverfront Park and Paul deserves a lot of credit for that. But I’ll take a little credit for it and but Paul really does deserve a lot of credit for it so that that see that led me to get involved with the parks and recreation department.

At that time, I was appointed by a mayor who was subsequently recalled I’m not going to mention his name because I don’t want to get into involved about the political situation in the town that’s not conducive to what I really would like to talk about. But you and I both know that there was a lot of recall activity in the history of our town but any rate he got recalled and he had appointed me to an organization at the time that was called the arts advisory board and this had been started by a couple of ladies who wanted to bring the symphony out and so forth so when I got there and when he got involved with the arts advisory board I could see some potential I could because when your town is small you can do a lot more things than you can do when the town is big you can get bills passed you can get things done faster when you’re dealing with staff and I needed to have some help though and I recruited a friend who became my best friend actually Robert Weede. Robert “Bob” Weede and I worked with the arts advisory board and we recruited several other people to be on the arts advisory board and by the mid-90s it was about 93 or 94 we started putting on events and these events were like festivals at the Riverfront Naranja Park didn’t exist at that time Jim Kriegh Park did but that was called Dennis Weaver Park at that time and we put on events at Riverfront Park and they would be fine arts festivals where we would get some of the fine artists from around the community and they were juried if you’re familiar with the term juried meaning that they had to submit their artwork and slides and we would review it and if it didn’t meet the our criteria we didn’t have them as contrasted to today where anything goes and it doesn’t play well with the public I don’t think that’s my personal opinion but we had a fine group of people working and we ended up with over a hundred volunteers wanting to help us with everything we did we had musicians who would come we had artists who would come people and they would help us we put up our own tents and lay out the chairs by ourselves we set up the microphones and when I was involved with the design of Riverfront Park I made sure that there was a little stage built so that we could utilize that stage for performances and also had an electric outlet that Sterling Electric put in free of charge and they ran the line from the stage up to the men’s room so if you wanted to turn on the electric you had to go up there to behind the men’s room turn on the electric but we started really putting on some wonderful events and then we moved some of them to what is now Jim Kriegh Park and we had some great events there and I could tell you story after story after story of things that happened we were always suffering by the weather one time we had an event where we had it scared me to death actually we had the artists all lined around in a row and we had food and there was a kettle popcorn place and there was a deep fryer guy there it was the one and only time we had a deep fryer but a dust devil came along and I mean a dust devil it picked up paintings and threw them across the road across Oracle from Jim Kriegh Park it just picked them up and threw them a woman we had a vehicle from Jim Click that was going to be auctioned off and the picked up a woman and threw her up against the car that’s how big it was. And it took all of that food and just threw it everywhere and the tents came down and it was really quite a happening. We had but we put it all back together it was a Saturday and we ended up on Sunday and oh yeah at that same event. We had the boys chorus from downtown Tucson and when the wind came along just the all the boys just the whole thing collapsed and the boys went down, they were singing but none of them got hurt; it was all a miracle. We had these various outdoor festivals and it developed a culture within the town and the beauty of it was the town council at that time was very supportive to at everything we were trying to do because they saw the value to it.

The one thing we were missing was we had no organization that was a nonprofit that could raise funds to do these things all of these things were being paid for either by us going out and getting sponsors, which is always tough, or the town and in fact at one time we were getting over $100,000 a year from the town but our budget at that time was 600,000. So, any rate I got together with Bob Weede one time we were sitting over at the golf course at the restaurant and talking and I said, “Do you know what we’re missing Bob?” And he said, “I know what you’re going to say.” And he did…we both said at the same time. “We need a separate arts council.” And right about that time we were able to get what was known as an art assessment from the Arizona Art Association. they send two women down to go around the town doing an assessment and they would hold public meetings and one of the more hilarious meetings and I do say hilarious was up at Sun City they had this big sign come to the art assessment meeting so the place was jam-packed it was just full of people and they thought assessment meant tax so when we announced what the real purpose of the meeting was half the people got up and walked out it was the funniest thing you ever saw here so anyway they did this to rock the town and they published a report and I have it in the car if you want to see it I meant to bring all that stuff in there it is this report was very comprehensive and there were two things that they s they really said we should be doing because of this way the town was we were a building town doing all kinds of construction commercial and so forth and so on and he said “One is you should start an arts council a nonprofit arts council which would take over all of the things that the arts advisory board was doing and more so and do more things.” And the second thing they said was you should do a one 1% for public art okay so that was in this report and as luck would have it, I was appointed to the general plan of 1996. We had a fellow who was the community development director by the name of Don Chapfield. Don Chapfield probably left his mark on this town more than just about any other employee I can think of he was open-minded he was very forward-thinking he was just terrific and when I talked to him about it he loved the idea of the 1% for public art and he took the lead on that thing but the first thing we did was I wrote a letter to Mr. Loomis and I told them I would like to form an arts council and as luck would have it they passed the idea that we could do it. So, we formed an arts council and that was in 1997 and that took off—it really took off. It did well. We did educational programs for kids in the schools; we brought the symphony out to perform on a regular basis. We had a full concert series for many years. Most of them were held at CDO High School, but some of them were held at St. Andrews Presbyterian Church and some of them were even held at Ironwood Ridge too. But we always had a full-blown concert series and it was terrific.

And the biggest single event ever held in Oro Valley—and I know it hasn’t been topped—was in 2003. We had a Fourth of July celebration, and we brought the symphony out to CDO Riverfront Park. And at the same time, we had arranged with the hotel. At that time, they were shooting off fireworks every Fourth of July because they had their own celebration. And we went to them and talked to them, and they said, “Uh, would you coordinate the shooting of the fireworks because we have the symphony coming and they’re going to play the 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky?”

And in the Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture, there is a spot where cannons go off. And real cannons were used by the Boston Symphony—that’s where I got the idea. I thought, well, what the heck? We had cannons where we could shoot off fireworks. So, we arranged with the hotel that when—at a given time—we had cell phones that they would, I’d say, “Okay, shoot.” And right at the point in the symphony, and it was wonderful—it was fantastic.

But there was one problem—they forgot to turn on their phone. And I kept calling, “Come on, come on.” I was trying to set up early, and I jumped into my car and I drove 80 miles an hour all the way back up to the hotel. And I got there just in time for them to shoot off the fireworks with the cannons in the symphony. And I—it was lucky I didn’t get a ticket, because there were cops all over the place and I was speeding like crazy. That’s what was part of the stuff that happens to you when you do this kind of stuff.

But there were 8,000 people—and that was the police count, not my count—8,000 people crammed in on soccer fields. And there, they had parking up and down Lambert Lane, but we also ran buses over to Casas Church and also down by the Fry’s store where people could park their cars, get on the bus, and come to the concert. And we did two of those, obviously, in order to handle it.

But those are the kinds of things that we did. And we did art shows in the town council where we paid prizes—we gave away first prize, second prize, third prize—and that encouraged local artists to get involved. There is a huge, huge element of artists in Sun City. And a good friend of mine, Dave Dame, who was the chief designer for the National Parks and quite a painter in his own mind, he joined our board. And he was a big influence on us getting artists.

In fact, he was so influential, he got us to join what is called the Southwest Art Organization, where artists from all over the Southwest—New Mexico, California—they would come to our festivals, they would submit. And that’s how professional and how great our festivals were. They were really first-class festivals.

So that went on for quite a bit of time, and I was getting older at that time. And we got to about 2005 and we interchanged presidents, and we kept doing different—a lot of education stuff for kids, a lot of instructional things. We got the sense we needed to go into the schools and have music classes for the various music schools, and they loved it. They just thought it was the greatest thing.

But as it got bigger and bigger, we ended up in 2005 with a budget of $600,000. Here we started out with $2,000—which, by the way, was a loan from the Tucson Pima Arts Council, which doesn’t even exist anymore. They gave us $2,000 to start, to build that. But by 2005, it was obvious we had to do something. I was getting older, and I recruited some people and we hired a bunch of staff to do it. And I took—at that time, I retired with a budget of $600,000.

So, a new team came in. And what has happened is another story which I won’t get into because I wasn’t involved per se in it. But that was my history trip—of my history with the arts council.

Around ’97, we had—this is a year after the general plan had included having an arts council and the 1% for public art. Well, I wrote a letter to council saying we need to implement the 1% for public art because it was part of the general plan. And it was pretty well received. And there was some objection on the part—I remember there was a fellow—I won’t mention his name—but he was a land developer who was opposed to it. He didn’t like the idea. But the council approved it.

And what we did—we took the bull by the horns, and we had a fellow there, Jim Copus, who was a staff member. And Jim essentially wrote the code, and I kind of reviewed it and made some changes, but he wrote the code. And he and I decided to put on some, for lack of a better term, educational seminars for builders.

And I thought, well, nobody will show up. Well, the mere fact that it was 1% for public art was enough—they filled the room. We had all of the top builders—P.Y. and all of them—and some of the heavy commercial. See, the 1% didn’t apply to residents; it only applied to commercial.

So, at any rate, they filled the room. And when we got through explaining it, I was amazed—there was only one person, and it was that same person who was objecting to it. David Mehl of Cottonwood Properties, a very prominent man—still a prominent man—was totally in favor of it and was very, very, very supportive. And we had others—Don Diamond, his people were all in favor of it, supportive of it.

So, it was a very exciting time. And when the art started, of course, the art had to be reviewed. And we had a commission to do that, and they did that for some years. And then they did away with the commission and let CDR—the Design Review Board—approve the art.

But we built quite a substantial lot of art in the town. And I have a book that we were able to produce from a $2,200 grant from the federal government—the NEA. Went out and made a total booklet of the art that I have. And I’ll bring that in and show it to you. I’ve been—I cornered a lot of them in my garage, and nobody wanted them. So, I kept them.

And I did it on purpose, because I wanted to use them as rewards for people who supported public art. And I got the town’s permission to do that. The town manager at that time—we were celebrating him—was Greg Cate. And he said, “As long as you build it that way.” And that’s how I’ve done it. When people did something good for the kids and so—I’ve got virtually none left, because we gave them all out to people who were supportive.

And so public art took off. And it became quite a thing. And in fact, it was so good that the town was nominated for an award for the best public art in a small town—that was some years ago. Some of the art is iconic. It appeared on airline magazine covers. It gave us a lot of attention.

Well, about the same time, about 2003–2004, there was a lot of activity. And Paul was involved in this himself—Paul Loomis—when the lands, the state-owned lands, became available. What is now Naranja State Park—Naranja Park at one time was an asphalt plant. And the plant really built most of the roads around here in the area, and even some of the highways—Oracle and so forth.

And it got to the point where they were so involved around the housing areas, it didn’t make sense for them to be there anymore. So, the state, I’m sure, moved in and told them to stop.

The interesting thing was, there was a lake on that property. There—in fact, the dam is still there. If you go walking, you can still see it. And there was a flat area up there where the offices were. It’s about two and a half, three acres. But the entire acreage is over 200 acres.

And we had at that time a committee that—Al Kunisch who was a former council member, oh well, he was a council member at the time, called me up one day and he said, “I need your help.” And I said, “What do you mean?” He says, “I want to form a committee and I want you to chair it.” And I said, “I’ve chaired enough stuff, I don’t need any more chairs.” So, he said, “Well, come on the committee.” And I said, “Okay.” So, he recruited Pat, who is one of the founders of the historic society, myself, Jim Kriegh, the town founder was on it, a fellow by Richie Fineberg, and there was a lady, Carol Baker. There was a group of us who formed what we called the Land Conservation Committee.

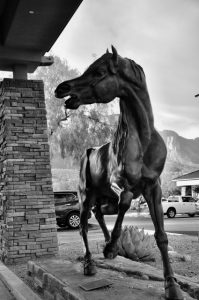

And it was an interesting group from the get-go because there were two things that really concerned us. One was the acquisition of the Naranja Park area—that is now Naranja Park—and the other was Steam Pump Ranch. And Steam Pump Ranch at that time was going through the throes of the family didn’t know what to do, they were selling off this and selling off… There were two brothers who ended up owning it at the one at the end. And there was a movement afoot by one of the owners to sell it to Brake Masters, and Brake Masters was going to build a facility right where we’re sitting, probably in this area right here.

Well, that’s one of the reasons we formed the committee. And there was a builder by the name of Nafy, and he started out being obnoxious, but when we started working with him and telling him what could happen, blah blah blah, and the town council was very supportive at that time also with that. But we would have meetings with him. I remember going to lunch with him twice, and somebody leaked it to The Star, and The Star wrote up the fact that I went to lunch with Nafy.

Well, I got a hold of The Star and told them why I went to lunch with Naffy, and they became a cause celebrator in our favor, and the Explorer picked up on it, and they wrote articles supporting our committee on this. I have some of those articles in the car. So, to make a long story short, we were able to stop him in his tracks with the town council’s support, obviously.

And at that same time, we were putting together—when I say “we,” the town with the county—was putting together the famous bond issue which brought us Naranja Park and Steam Pump Ranch and a thing called Kelly Ranch. Kelly Ranch is at the end of Rancho Vistoso Boulevard. Across the street, there’s a white fence, and on that property, it’s about 200 acres, I believe. There’s a Joesler house sitting right smack in the middle of that place, and the older town council used to go up there for retreats and stuff. And it stopped. For whatever reason, I went in there by myself and I almost got shot. The guy came out with a shotgun. He said, “What are you doing here?” And I was trying to look it over, you know, because I knew it was on the bond issue.

And I could see what the problem was. It abuts up against Catalina State Park, so the obvious restrictions on the park would limit the development of the property too. And at that time, before it was Pima County—Pima County zoning—so those three things were on the bond issue.

And we worked—that is, the Land Conservation Committee worked—very, very hard. And so hard that we got signed by the county attorney. And the reason is very simple: one of the council people who were running for office asked us if she could put a squib on her materials about the bond issue passing. And we—you know, naive, dumb us—we didn’t know, so we said, “Oh well, okay, go ahead.”

So here we are, and I get this phone call from Barbara Lawl, says, “Mr. Eggerding, I hate to tell you this, but you’re violating the law.” And so, what happened was there was a $1,500 fine, and the ten of us put up 150 bucks and we paid the fine. But it is true that those people can’t back a bond issue. It takes a, like us, a bond committee that has to do it.

Well, our work paid off. Not only our work, but a lot of work by a lot of people paid off, and we did end up with the property. And that was very, very exciting. I was chosen to be the chairman of the Naranja Task Force after the bond issue. That was a very interesting time. There was a whole bunch of prominent people in the town. General John Wickham was part of that group. He was chairman of what we would call the Executive Committee, and I was chairman of the Task Force.

And we interviewed 125 stakeholders—people who wanted to use that park. It was amazing. And we were so pleased to have the park. And unfortunately, as the case were at the time, the town couldn’t afford to do what it—what the amount of money was at that time. And it’s been faced with that issue from the get-go. We had some wonderful designs to do things, rec, performing arts center, whatever, and you know, you can argue those things all day long. So, what’s happening now is that we’re doing it a step at a time, apparently, and that changes with the councils—different councils.

But it’s exciting that we own the property. Naranja Park is a gem. And this, I meant to mention to you earlier—these are little tidbits: the Jim Kriegh Park was originally called Dennis Weaver Park. Dennis Weaver Park was not named after the movie star; it was named after a county supervisor who happened to oppose, by the way, the forming of Oro Valley. He was opposed to it. So needless to say, we did the right thing changing the name from Dennis Weaver and calling it Jim Kriegh, who was the town founder.

Another interesting story—and people challenge me on it, but I got the poop card for it—Lambert Lane is really called after Lambert Kautenberger. Lambert Kautenberger. was a county supervisor, and he opposed the town being formed. Ironic: his son, Bill Kautenberger., became a town council member many years later. Another little tidbit of that.

So, the parks were important, a lot of activity going on at that time. One of the things that I got involved with General Plan was on the committees. I was able to get on committees to—we got various codes passed about “Save a Plant,” things like that. I don’t take credit for it. I was just a member of the committee. “Save a Plant,” the idea of putting in trails, the idea of having bicycle paths, the idea of design elements that buildings had to have—pop-outs around the windows, that type. I could go on and on.

Oro Valley looks like it does today because a lot of hard work that was done by town council people and volunteers in the early 90s—I mean, the late 90s and the early 2000s. A lot of hard work, but people who had to stick to their guns, because we had a lot of people didn’t want to do a lot of things that we wanted to do. And so, we can be very proud of the way our town looks today because of the efforts of volunteers and the council.

I think it’s important to understand how some of these things evolved that happened in the town. Like, for example, the forming of the historic society. The three of us who formed the society—Jim Kriegh, Pat Spoerl, and myself – got to know each other early on because of our work with the Land Conservation Committee. So, we really became good friends. And it was Jim Kriegh’s idea, by the way—it was his idea to form the historic society.

And one of the concerns that Pat Spoerl had in particular was getting national designation for the property. And that was important also. But to make a long story short, Jim Kriegh called Pat and I together, and we met on a number of occasions on how to go about this and form the historic society. Tobin Sidle, the town attorney, is a good friend. He was a big help doing some of the pro bono legal work—off hours, not on hours, on his own. I asked him to help us, and he was a help to Jim. And Jim was having some trouble getting all the proper documentation for the IRS, etc., etc. But we finally did get it, and it was a big, big day for us to get the historic society.

And we also ended up getting the national designation as well. And one of the requirements for getting that designation is you had to have a historic commission. And that’s why you see today that we have this historic commission.

I don’t wish to make an editorial comment, but there are times sometimes when the historic society’s duties and elements are confused with the historic commission by the public, and they’re vastly different. The historic society is really a true nonprofit, and it needed to have the assistance of the town. So, once we got it, we were able to get a master operating agreement with the town, which allowed us to do a variety of things—to get into this house and so forth—and what you see today, a lot of it evolved because of the formation of the historic society.

The unfortunate thing about the society: it’s always struggled to raise funds. It’s always been an issue. And it’s always been an issue: should the town give funds for the master operating agreement? Well, yes. In my opinion, they should. But it’s an area that has to be addressed fully, and more can be said about that later on.

But in essence, the town—the society took off and did a lot of things in rehabbing—getting rehab money from the bond issue. Some of the stucco work on this building was really in poor shape. And bear in mind, the county was involved with the bond issue, so this property, in some instances, you can’t make any major changes really, and we were taught that without their giving their approval.

Now, I don’t know how much that’s been debated or argued, but it kind of was held up that we had to have them involved. And there was a wonderful lady over at the county who was very, very helpful, so we didn’t really have a lot of trouble getting things done. But we needed to get money from the bond issue. So, since it was a county bond issue, there was some money released for rehabbing this area, and that was good. That part of it was good.

The unfortunate part still with the society is that it still hasn’t gotten the financial support that it should. And there are a lot of things going on—like, we should be addressing the rehab of the house over there and continuing to rehab this house, and there should be an overall project that comes forth.

And there was a committee put together to do a redesign, if you will, and rehab of the entire area. And I have that booklet out in my car too, I meant to bring it in—I’ll show it to you. I was appointed to that. It was a huge committee, and they came up with a terrific design plan. But it would require a bond and town support, and the town just never did it. And it’s still there, and it still should be done, because unfortunately, the time is going to come when that property is going to deteriorate to the point where it is beyond rehab—just like the Steam Pump house.

See, when you have that national designation, you can only do so much that isn’t the original. You have to—whatever you’re going to rebuild, you almost—you have to use the rebuilding material that was there. Therefore, you don’t see the completed pump house, for example. But we were able to salvage enough of the material to rebuild what is out there.

And the interesting thing about the Steam Pump—a lot of people aren’t aware of—that pump came from Germany by George Pusch. And something happened to it in the interim, but down in the basement of the Arizona Art Museum downtown, in the basement is a steam pump that’s very similar to the one that was here at the ranch. There’s an argument that that is the original, but I don’t think it was. But there’s a debate always going on. But that’s sitting in the basement. And there is original Pusch family furniture sitting down there on exhibit. There is a thing—I think they call it the Pusch Room—and it’s got all the furniture from here.

And I asked them one time, “When can we get that furniture?” And they said, “When you got $5 million, and you got a proctor.” So, you have to have $5 million and a proctor, and they’ll release the furniture. I thought that was unfortunate, because it really belongs out here.